The petty court sessions of the 19th and early 20th century Ireland formed a cornerstone of the local judicial system. These sessions, typically held by justices of the peace (JPs), were central to rural and urban governance, providing a relatively accessible and cost-effective means of maintaining law and order within communities. The courts were key in addressing minor legal disputes and criminal matters. They dealt with a wide range of cases, from petty theft and public disturbances to civil disputes over debts and property. The courts had limited but significant powers in dealing with minor criminal and civil matters. These courts functioned as the lowest level of the judicial system in an Ireland under British rule. Their jurisdiction covered summary offenses, meaning cases were dealt with swiftly without a jury. In County Cork, there were regular petty court sessions in several locations – e.g. Cork City, Cobh, Midleton, Youghal and Castlemartyr. In the available records, which in entirety span over 100 years, there are 1,272 instances where a person from Ballymacoda was either a complainant or defendant. The vast majority of these – 1,179 – were heard at the petty sessions in nearby Castlemartyr and there is a wide range of complaints and offences captured. In this article, we will look at some of these court reports from yesteryear.

Some of the offences were extremely minor, and we may think somewhat laughable today. In a November 1879 case, Maurice McCarthy of Ballymacoda’s cause for complaint was ‘trespass of the defendants six cows in complainants garden at Ballymacoda on the 30th October 1879’. The defendant in the case is John Hennessy of Ballymakeagh, and he was ordered to pay McCarthy six shillings and pay his costs. There are actually numerous examples of this offence of trespass of cows in the records.

Another example of a minor offence by today’s standards of what we may see appear before a court is the case of Michael Walsh, Knockadoon. The complainant in his case, Michael Driscoll, also of Knockadoon, stated that the defendant ‘did deposit a quantity of seaweed on the public road leading from Ring to Knockadoon’ which was a danger to the public. There was no appearance by the two men on the date of the case, June 19th, 1885, so one can only postulate that they resolved their differences amicably.

One of the most common offences occurring in the records is individuals being fined for drinking on a Sunday or the publican being fined for having been open when they should have been closed. An example of this is the petty sessions held on October 15th, 1886. At these sessions Ellen Power was fined for ‘having her licensed premises at Ballymacoda open for the sale of intoxicating liquor on Sunday the 5th December 1886’. Along with the publican herself, John Donohoe of Gortavadda, William Aher of Ballymacoda, Mary Lynch of Ballymacoda, and Mary Brien of Ballyfleming were fined for being present in Power’s public house on the same day. Interestingly, Ellen Power was fined one shilling for being open and one shilling costs, while the four customers who were present in the pub were given a larger fine of five shillings each and one shilling costs.

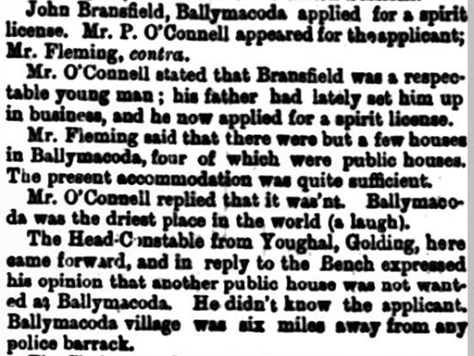

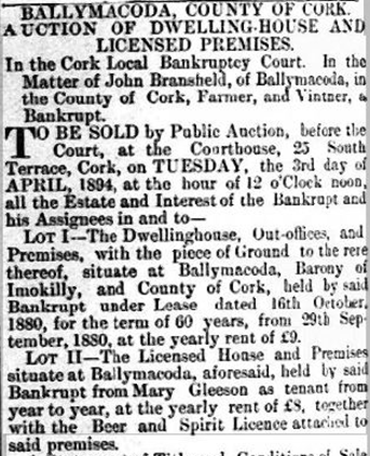

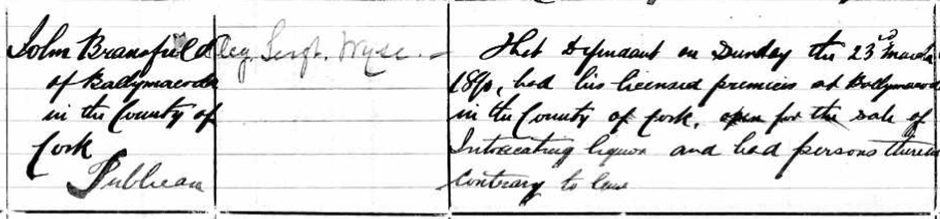

Another example of this offence in the records is the publican John Bransfield, who was fined twenty shillings for having his premises in Ballymacoda open on Sunday March 23rd, 1890. Bransfield was before the court for the same offence again on December 23rd of the same year, and again in May 1891.

Another common occurrence in the court records is that of the defendant being drunk in public. An example of this is the case of Maurice Smiddy of Ballymacoda. At the October 18th, 1887, sessions in Castlemartyr, he was fined 1 shilling for being drunk in Ballymacoda on October 5th. He was also fined 1 shilling for costs. If he did not pay, he was to be confined to the County jail in Cork for 48 hours. The late 19th and early 20th century equivalent of drink driving is also common in the records. An example of this is the case of Michael Gumbleton of Knockadoon, who at the petty sessions held on November 2nd, 1897, was charged with being ‘found drunk in the charge of a horse and car on the public road at Yellowford’. He was fined 2/6 and ordered to be committed to Cork prison if he didn’t pay.

Something else that is hugely common in the records of the petty sessions are cases where a complainant is seeking money which they are owed. The Petty Sessions (Ireland) Act of 1851 allowed for the recovery of small sums, and cases were often resolved swiftly compared to higher courts. Judgments could result in payment orders or even seizure of goods if the debtor failed to pay. One name that comes up quite a bit in this context is William Aher from Ballymacoda, who was a shoemaker. Over the course of at least fifteen years there are numerous examples of Aher having to use the petty sessions to obtain what he was owed for the work he had completed. The effectiveness of the petty sessions in recovering debts for individuals and businesses was mixed. On one hand, the courts provided a relatively quick and inexpensive means for creditors, such as landlords, shopkeepers, and tradespeople like William Aher, to pursue unpaid debts. However, enforcement was a major issue. Many debtors were simply too poor to pay, rendering court rulings ineffective. Sheriffs were responsible for enforcing debt collection, but in cases where the debtor had no assets, the creditor was left without recourse. Historians such as Fergus Campbell (Land and Revolution: Nationalist Politics in the West of Ireland, 1891–1921) have noted that the system often favoured landlords and wealthier individuals, making it less effective for poorer claimants trying to recover money from equally impoverished debtors. As a result, while the petty sessions provided a legal avenue for debt recovery, their actual success depended heavily on the financial circumstances of the debtor and the efficiency of local enforcement mechanisms.

At the sessions of August 22nd, 1879, there are several cases relating to ‘unjust measures’ and ‘unjust weights’. Ballymacoda Publican Philip Walsh was fined for having ‘one unjust and illegal measure’ on his premises. The spirit measure in question also had to be forfeited. Publicans in nearby Mogeely, Michael Hartnett and Thomas Kenefick, were also fined on the same day for the same offence. Ballymacoda shopkeeper Martin O’Driscoll was fined the same day for having ‘two unjust weights’ in his possession. There are also defendants from Ladysbridge, James Thompson and William Coughlan who were fined for having unjust weights in their possession. The complainant in all these cases is the same – RIC Constable Terence Prendergast of Castlemartyr. One can only assume that he made it his business to visit local pubs and shops and perform checks on the measures and weights in question.

People from Ballymacoda also show up in the records of other petty court sessions held throughout Cork. An example of this is John Cronin from Ballymacoda, who appeared at the Kinsale sessions on September 5th, 1896. He was listed as a ‘R. N. Reserve man’ (member of the Royal Navy Reserve) and was charged with being found drunk in the public street in Kinsale on August 22nd, 1896.

In tracing the stories of Ballymacoda’s inhabitants through the petty court sessions, we catch a glimpse of both the ordinary and extraordinary elements that shaped daily life in late 19th and early 20th century Ireland. These courts were more than just a forum for settling small-scale disputes; they played a pivotal role in preserving social order at a grassroots level. Offences ranged from the trivial – like trespassing cows or seaweed left on the road – to the more universally recognized issues of public drunkenness and not paying one’s debts. The petty sessions enabled ordinary people, such as shoemaker William Aher trying to recover unpaid bills, to seek redress without the expense and complexity of higher courts. Yet the system, under the governance of justices of the peace and local constabulary, reveals much about power balances in rural communities. Often, wealthier individuals and landlords had an advantage, both in bringing lawsuits and securing a favourable outcome. Meanwhile, the poorer segments of society – those who might have little to no assets – faced legal rulings they could hardly afford to honour. Still, the very existence of these sessions offered residents an alternative to vigilantism and personal retribution, encouraging negotiation and, at times, informal resolution.

Today, these records stand as a fascinating archive of local history. They illuminate how government, law, and ordinary people interacted in a rapidly changing Ireland. By examining cases from disputes over livestock to the regulation of alcohol, we gain not only a window into the practical workings of petty courts but also a richer understanding of the social fabric that held communities like Ballymacoda together.

References & Further Information

Ireland, Petty Session Court Registers, 1818-1919

Fergus Campbell, 2005, Land and Revolution: Nationalist Politics in the West of Ireland, 1891–1921