Rutland, Kane County, Illinois, USA

Catherine (née Long) & John Cullinane were a married couple from Ballymacoda who emigrated to the United States in the 19th century. From humble beginnings, the Great Famine forced them to emigrate in 1847, and they were to eventually become owners of a large tract of farmland in Illinois. Their surname ‘Cullinane’ would go through various changes in spelling on official documents of the time as we shall see, with it ending up being spelt as ‘Clinnin’ by the time John & Catherine passed away. This was not uncommon for the time given the low literacy rates, with many people who could spell, spelling a name as it was pronounced and thus a surname evolving in such a manner.

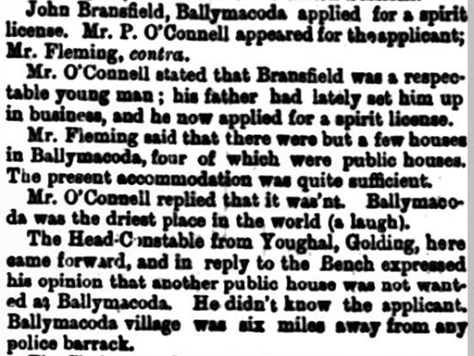

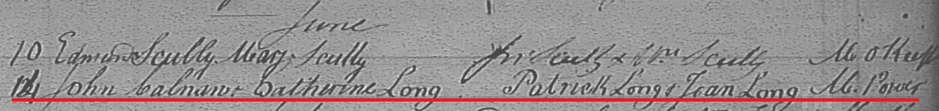

Both John (known as ‘the red’) and Catherine were born in Ballymacoda – Catherine in 1815, and John in 1817. Catherine was the daughter of James Long & Catherine Lee. John was the son of James Cullinane and Ellen McCarthy. The Ballymacoda Parish marriage records show that John & Catherine were married on June 14th, 1838.

In 1847, during the worst year of the famine, John, Catherine and family emigrated to the United States. The year is corroborated by an entry in the 1900 United States Federal Census, in which Catherine, now living in her daughter’s household since John’s passing, confirmed her year of arrival in the United States as 1847. Their arrival in the United States in 1847 is also corroborated by the first trace of the family we find in America in the historical record – this is in the 1850 United States Federal Census.

The data in this census, three years after their arrival, shows John & Catherine living in the Grafton Township in McHenry County, Illinois. John’s occupation is recorded as farmer. This region, having recently been settled, was originally settled as a farming community. Fertile fields and dedicated labour by emigrants led to abundant harvests, enabling local farmers not only to supply nearby creameries but also to ship milk to processing plants in Chicago. Grafton lies in the southern part of McHenry County, bordered on the south by Kane County, on the east by Algonquin, on the north by Dorr, and on the west by Coral. In the 1850 US census, John & Catherine are recorded as having three children – Ellen, Hannah, and Catherine. Also noteworthy in their 1850 US census entry, is that their surname is once again misspelt, this time as ‘Clynnen’ – here we can start to see the progression in the morphing of the surname from ‘Cullinane’ to its final ‘Clinnin’ – with the latter still being used by the many descendants of John & Catherine today.

Fast forwarding ten years to the 1860 United States Federal Census, we find our next trace of the lives of John & Catherine. By this time, they are living in Rutland Township, in Kane County, a little south of where they were previously recorded as living in the 1850 census. John is again recorded as a farmer, and it is possible that the move south was due to better opportunities to procure land – his obituary refers to him owning 200 acres in that area by the time of his death. The obituary of their daughter Mary in 1910 also mentions that John & Catherine were ‘among the earliest settlers of Rutland township, obtaining their land from the government’. Their location remains the same in the 1870 United States Federal Census, and by this time five children are listed as present – Catherine (aged 21, a dressmaker), James (aged 19, a farm hand), Mary (aged 17, whose occupation was recorded as ‘housework’), and John (aged 13) and Margaret (aged 9), whose occupations were recorded as ‘at home’. The oldest children – Ellen and Hannah are not recorded in the 1870 US census entry, likely because they no longer lived at home and now had their own families.

Likely, John and Catherine began their American journey with little more than hopes, dreams, and the determination to build a better life for themselves and their family in America, having left the hardship and poverty of the famine at home in Ireland. As recent emigrants, they may have started by renting or labouring on smaller plots of land, gradually learning which crops thrived and which methods brought greater yields. Over time, thrift, steady work, and an astute sense for opportunity likely enabled them to increase their holdings and livestock and invest their profits back into the farm. The favourable farmland in their chosen destination, combined with economic demands for dairy products in nearby Chicago, would have provided them with both stability and prosperity. As they raised their children, tended to livestock, and steadily expanded their acreage, John and Catherine’s reputation as successful landowners grew. By the time of their deaths, they were no longer simply emigrants from Ballymacoda making a go of it in a new country, but rather respected, wealthy figures who had helped shape the community’s agricultural landscape and left a legacy that extended through multiple generations of their descendants.

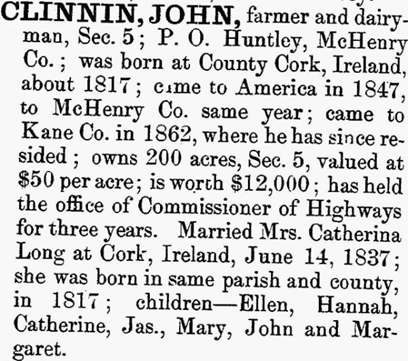

John Clinnin died on July 3rd, 1884. His obituary, seen below, was carried in local newspapers, ensuring that news of his passing reached a wide audience in the surrounding community.

By this time, it was mentioned that he owned 200 acres of farmland and was worth $12,000, a considerable sum of money for that period. Such an amount would have placed him comfortably among the more affluent members of society, reinforcing the notion that his estate and possessions were well beyond the common standard of wealth. This notable financial standing, coupled with the substantial size of his landholdings, indicates that John Clinnin held an elevated position within the social and economic fabric of his era. It was also noted in his obituary that John had held public office as Commissioner of Highways for three years.

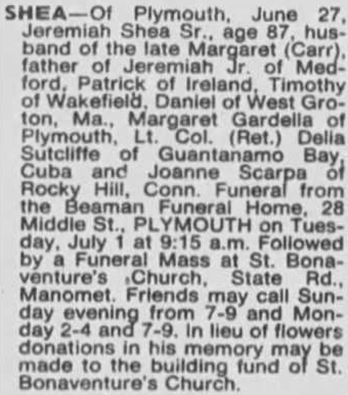

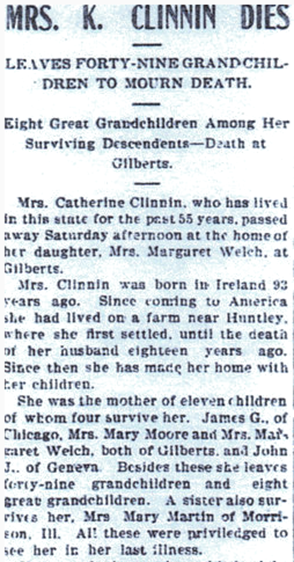

After John’s death, Catherine eventually went to reside with one of their daughters, a move that likely reflected the changing circumstances of her later life and the close-knit family ties that provided comfort and stability. Catherine’s obituary not only serves as a record of her passing but also offers significant data regarding the fate of the couple’s children. By the time Catherine died on August 10th, 1902, only four of their children were still alive, a poignant reminder of the era’s elevated mortality rates and the fragility of life on the American frontier. Both Catherine and John were buried in Saint Marys Cemetery in Huntley.

Furthermore, the obituary makes note of Catherine’s extensive lineage, citing a remarkable total of forty-nine grandchildren. One of these grandchildren, as we shall see later, was destined to play an especially notable part in preserving the family’s legacy, shedding further light on the enduring impact that these Ballymacoda emigrants had on their country of destination and the generations that followed.

Based on my research into John and Catherine Clinnin, it is likely that they were the ones who first introduced the ‘Clinnin’ surname to this region of America – as we have seen, this is a morphing of John’s original surname of ‘Cullinane’. There are countless examples of the generations that followed, right up to the present, using this surname. Another interesting find is that there is a laneway called ‘Clinnin Lane’ in the village of Huntley, just north of Rutland – I would be extremely surprised if this wasn’t named after a descendent of John & Catherine Clinnin from Ballymacoda.

The descendants of John and Catherine’s son, James Clinnin, would find themselves closely tied to numerous significant historical conflicts. James married Jane Dougherty, a native of Nantucket, Massachusetts, on New Years Eve 1874.

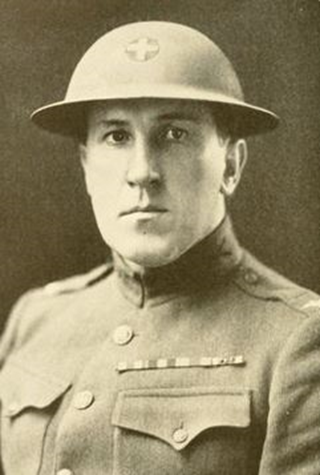

Their first-born son, John Vincent Clinnin (grandson of John & Catherine), would go on to become a well-known figure in Illinois and the United States in general. He was heavily involved in the sport of boxing, being at one time chairman of the Illinois Boxing Commission and president of the National Boxing Association. He was also an accomplished lawyer, who became an Assistant US Attorney, and practiced law in Chicago. He also ran unsuccessfully for the position of Lieutenant Governor of Illinois in 1936 and 1940.

But it is his wartime service that is probably most notable. He had a distinguished service in the US Army – being awarded the highest honours possible – the Distinguished Service Medal, a Bronze Star, and a Purple Heart. He was Commander of the 130th US Infantry during World War 1 and ultimately attained the rank of Major General. He died in September 1955 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia with full military honours.

The son of John V. Clinnin, John Vincent Clinnin Jr., also served the United States, fighting with the US Marine Corps during World War II and the Korean War. He also received a Purple Heart and also had the honour of burial in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. There are not many father and son pairs in US history who have both received a Purple Heart.

It is truly remarkable to consider that the descendants of two emigrants from Ballymacoda established such a distinguished record of service in the United States. From the quiet beginnings of a modest farming endeavour to the eventual accumulation of expansive landholdings, their journey embodies the promise and opportunity that America offered to those Irish emigrants who worked hard and took risks. Over time, these individuals would become deeply entwined with major historical conflicts, their contributions helping to shape the broader narrative of the nation. Their story, spanning multiple generations as we have seen, highlights the resilience, adaptability, and community-minded spirit that our emigrants often carried with them as they wove their legacy into the very fabric of American history.

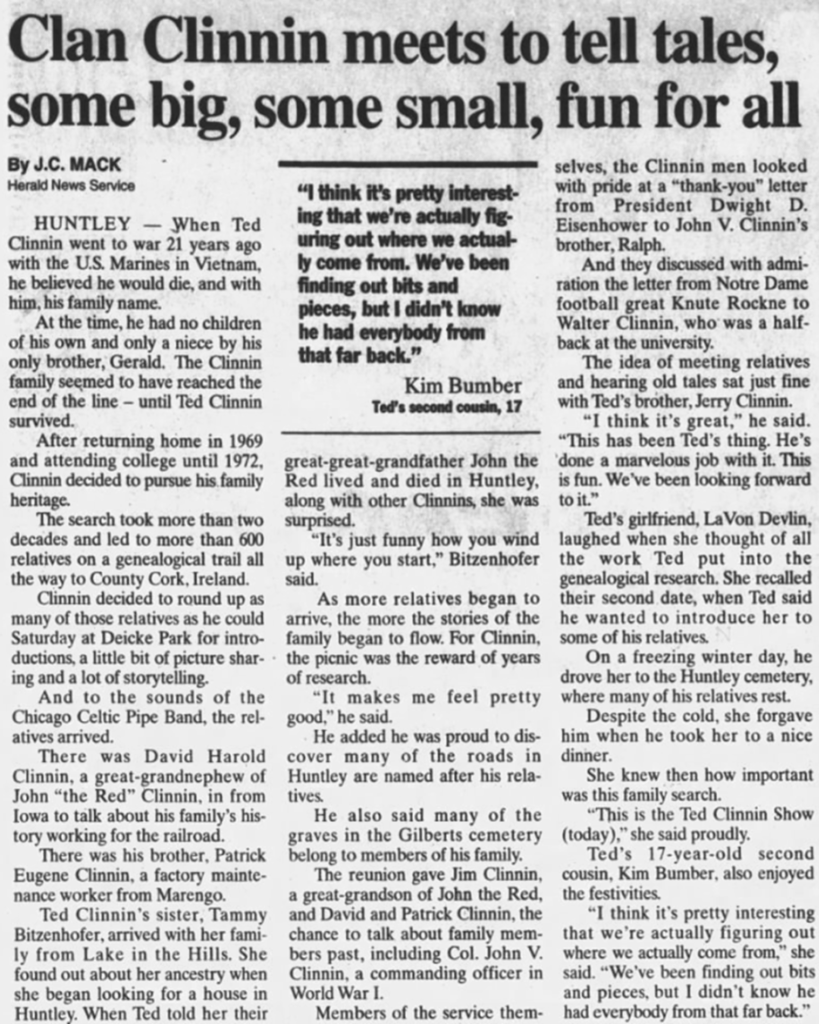

Seen below, an article that carried in the Northwest Herald, in Woodstock, Illinois on Sunday, August 23, 1998, regarding a large Clinnin family reunion – all descendants of John & Catherine who left Ballymacoda in 1847 to seek a better life.

References & Further Information

Ballymacoda Parish Records

1850 United States Federal Census

1860 United States Federal Census

1870 United States Federal Census

1900 United States Federal Census

Google Maps

Northwest Herald, Woodstock, Illinois, Sunday, August 23, 1998, Page 17