The more time I have spent delving into the stories of emigrants from Ballymacoda, the more firmly I am convinced that I have only begun to scratch the surface of the most interesting tales. It seems that, despite the passage of generations, only a small fraction of these remarkable stories has ever reached a wider audience, leaving countless individual journeys forgotten. One such journey belongs to an emigrant from Knockadoon, Ballymacoda – Jeremiah Shea – whose path in life took a truly unexpected turn. Far from the familiar coastline of East Cork, he found himself in the orbit of one of America’s most prominent figures, ultimately marrying a woman who was counted among US President Calvin Coolidge’s favourite cooks.

Two pieces of evidence in official United States documentation relating to Jeremiah point to a birth date of July 22nd, 1892. These documents are his World War 2 draft card, and his US naturalization application. Jeremiah’s gravestone also lists his birth year as 1892. Jeremiah’s mother was Norah Shea, and she is listed as a widow in both the 1901 and 1911 Census of Ireland records. Norah lists 8 children, 7 of whom are still living in her 1911 census entry.

There is documentary evidence suggesting that Jeremiah enlisted in the Royal Naval Reserve as a young man and saw active service during the tumultuous years of World War 1, gaining firsthand experience of the global conflict that reshaped the European continent. His Royal Navy medal record indicates that he received the Star (1914 or 1914/15), the Victory Medal, and the British War Medal for his wartime service. After the war ended, like so many others he sought new opportunities beyond the shores of his homeland. In 1920, he made the transatlantic journey that would forever alter the course of his life, departing from Liverpool, and arriving in New York on November 11th. The vessel on which he travelled, the SS Suelco, carried him across the ocean at a moment in history still reverberating with the aftermath of war. Stepping onto American soil in the bustling port of New York marked the beginning of a new chapter, one that would see him integrate into a different culture, forge lasting connections, and lay the foundations of a life far removed from the rural Knockadoon origins of his youth.

Jeremiah worked as a caretaker at the estate of businessman Frank W. Stearns adjoining White Court, seen here on the right. Located on the coast in Swampscott, Massachusetts, White Court became then US President Calvin Coolidge’s ‘Summer White House’ in 1925. He and First Lady Grace Coolidge spent the warmer months of that year there, escaping Washington, D.C.’s summer heat and humidity, while still carrying out official duties. The estate’s name stems from its grand, white, columned façade, and it was one of several locations to which Coolidge would retreat during his presidency to rest and conduct presidential business in a more relaxed setting. It was while working as a caretaker that Jeremiah met his soon to be wife, Margaret Carr during the summer of 1925.

Margaret Carr, like Jeremiah Shea, was an Irish immigrant. She had left Galway for the United States in early 1920. Margaret worked as a cook for the Coolidge’s at the White House in Washington, D.C. and was with them in White Court during the summer of 1925. There are references to Margaret being the President’s favourite cook. She had also worked as a cook for previous US President Warren G. Harding before he died in 1923, elevating then Vice President Coolidge to the position of President. Margaret and Jeremiah’s granddaughter recalls from family lore that President Coolidge was particularly fond of Margaret’s corned beef with cabbage, her beef stew and her apple pie. Margaret & Jeremiah were married on October 20th, 1925, at the St Francis de Sales Church, Bunker Hill St. in the Charlestown neighbourhood of Boston. Margaret had resigned from her position as the Coolidge cook shortly before the wedding. The couple honeymooned in Bermuda. After returning they made their home at 58 Main St. Somerville, located directly to the northwest of Boston.

The wedding of these two Irish immigrants in the United States – Jeremiah from Knockadoon and Margaret from Galway – drew widespread attention due to their unique presidential connection and the circumstances under which they first met. In a time long before modern social media platforms and instantaneous news updates, their union nevertheless achieved a level of notoriety akin to the high-profile weddings we might see splashed across the feeds of prominent social media influencers today. Major newspapers like the Boston Globe and the Washington Times carried reports on their nuptials, demonstrating just how fascinated the public was with every detail of their story. After their marriage, the granddaughter of Jeremiah and Margaret recalls that they opened a restaurant aptly called ‘The White Court Lunch’ on Bunker Hill St. in the Charlestown neighbourhood of Boston, where the bestseller on the menu was President Coolidge’s beloved apple pie.

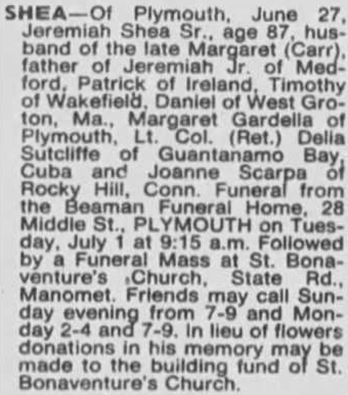

Jeremiah and Margaret had seven children, all born in Massachusetts – Jeremiah Jr (born 1926), Patrick (born 1928), Margaret (born 1929), Delia (born 1931), Timothy (born 1932), Johanna (born 1936) and Daniel (born 1937).

At some point, the family moved to 1 Snow Terrace in Somerville, just a few minutes away from their previous home. The 1940 Somerville city directory confirms the family living at this address, with Jeremiah’s occupation listed as chauffeur. The record of Jeremiah’s petition for US naturalization from November 9th, 1942, also lists his place of residence as 1 Snow Terrace. As mentioned earlier, this record also confirms his birth date of July 22nd, 1892, in Knockadoon. In addition, it confirms that he has never returned to Ireland up to this point.

Jeremiah Shea died in Plymouth, Massachusetts on June 27th, 1980, aged 87. Margaret had predeceased him, having died in August 1977. Both were laid to rest in Vine Hills Cemetery, Plymouth, Plymouth County, Massachusetts.

The story of Jeremiah Shea and Margaret Carr is emblematic of the uncharted chapters in the wider emigrant narrative of Ballymacoda – an extraordinary reflection of how far an individual’s journey can stretch beyond our shores. Their odyssey underscores the resilience and fortitude of countless others whose stories remain hidden in archives or family lore, waiting to be pieced together.

From Jeremiah’s beginnings in Knockadoon and his wartime service, through Margaret’s migration from Galway and subsequent work in two presidential households, their shared trajectory draws a vivid line from Ireland to the heart of American political life. Their marriage and the success they found – whether through their connections to President Coolidge, the bustling restaurant they opened, or the large family they raised – demonstrate that the pathways carved by Irish emigrants often crisscross continents and history alike. In doing so, they remind us that for every familiar tale, there are countless more to discover, each deserving to be chronicled for the role it plays in the ever-evolving tapestry of our diaspora.

References & Further Information

Ireland, Civil Registration Births Index, 1864-1958

1901 & 1911 Census of Ireland

UK, World War I Pension Ledgers and Index Cards, 1914-1923

UK, Naval Medal and Award Rolls, 1793-1972

U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942 for Jeremiah O Shea

Wikimedia Commons, Photograph of White Court

The Boston Globe, October 21st, 1925, Page 8, report on the wedding of Jeremiah Shea and Margaret Carr

U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995, Somerville, Massachusetts, City Directory, 1940

The Washington Times, October 22nd, 1925

Kai’s Coolidge Blog, available online – https://kaiology.wordpress.com/2010/09/20/a-coolidge-grace-that-is-dessert-recipe/

Massachusetts, U.S., State and Federal Naturalization Records, 1798-1950 for Jeremiah Shea