2025 marks 180 years since the onset of the Great Famine (an Gorta Mór), a tragedy that reshaped Ireland’s history and diaspora. The famine had a devastating impact on East Cork, reflecting the broader calamity that swept across Ireland. This catastrophic event was triggered by a potato blight, which decimated the crop that served as a staple food source for a significant portion of the population, estimated at roughly 3 million people in Ireland at that time. The famine led to widespread starvation, malnutrition, and a staggering increase in food prices, profoundly affecting our regions social and economic landscape. As families struggled to survive, the death toll soared, and many were forced to emigrate, resulting in dramatic demographic shifts that altered the community’s fabric forever. While emigration was the solution for some, not everyone had the means to emigrate, especially if that meant to America, where the cost of travelling across the Atlantic was prohibitive for the poorest of the poor people who were most impacted by the famine. While some assisted emigration schemes existed, for example the schemes financed by the Irish Poor Law Boards of Guardians, these schemes were not widespread or consistently available to all who needed them. Some landlords also contributed to the emigration costs of their tenants, but for vastly different reasons. In a few more benevolent cases, landlords genuinely wished to help tenants seek a better life overseas. More commonly, however, landlords viewed it as a cost-effective way to clear overcrowded and unprofitable estates by paying tenants passages to distant lands.

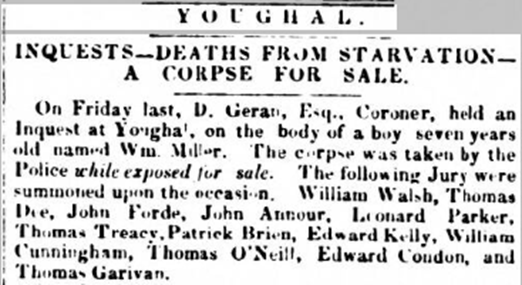

One of the most tragic stories that illustrates what the depths of the famine were like for those in East Cork who faced it, is that of a family from the townland of Ring in Ballymacoda attempting to sell the corpse of a 7-year-old boy, William Miller, in nearby Youghal, who had died from starvation in January 1847. The story of the inquest carried out into the incident appeared in numerous newspapers, including the Cork Examiner, and the details I present in this article are based upon reports from the time. The main people in the story as we shall see are:

- Daniel Geran – the coroner in the case

- John D. Ronayne – a chemist with a shop in the town of Youghal

- Michael Mangan – a sub-constable of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)

- Richard C. Ronayne M.D. – a doctor in Youghal

- Thomas & Johanna Miller – those attempting to sell the corpse of the boy

The inquest in Youghal was held on Friday January 29th, 1847. The jury of twelve men that was sworn in were: William Walsh, Thomas Dee, John Forde, John Annour, Leonard Parker, Thomas Treacy, Patrick Brien, Edward Kelly, William Cunningham, Thomas O’Neill, Edward Condon and Thomas Garivan.

The first witness to be called was the chemist, John D. Ronayne. He testified that he was in his shop in Youghal on the afternoon of Wednesday January 27th, when a man, identified in court as Thomas Miller, came in and asked him if he wished to buy a corpse. Mr. Ronayne, taken aback, enquired about the gender and age and was told by Miller that the corpse was that of a boy and that he was aged 7 or 8. Ronayne and Miller were interrupted when Ronayne was called to his own house, and when he came back to the shop Miller was gone. However, on inspecting the street, Ronayne saw an RIC man, and alerted him to the situation.

RIC Constable Mangan was sworn in and testified that when another constable was giving him the prisoner Miller after he had been arrested post the encounter in the shop with Mr. Ronayne on the afternoon of January 27th, he observed a woman, identified in court as Johanna Miller, as standing close by. On her back, she carried a basket which was covered with a black cloak. On inspection of the basket, Mangan found the body of a child. At this point, Constable Mangan noted that the prisoner Thomas Miller started to state why he had brought the child for sale and said that the child he had reared for the last six years was ‘an illegitimate child belonging to his sister’, and that ‘his mother was in England’.

Next called to the stand, was the doctor Richard C. Ronayne. He testified that he was called upon to examine the body of a young child at the police barrack in Youghal, ‘doubled up in a basket, and covered with straw’. During his examination, the doctor noted ‘not a particle of food to be discovered in the stomach or intestines’, and ‘the total absence of a dispose or fatty matter’. The doctor’s harrowing conclusion was that the boy had died of starvation.

Thomas Miller was next to be called to the stand. Described as ‘a wretched, emaciated looking man’, I am sure he was fairly typical of the time when the poorest of the poor were starving. Miller, of Ring, Ballymacoda, then began his testimony to describe how this heartbreaking event had come about.

Miller, as he testified, had been employed by Mr. Gaggin of Greenland for the last 10 years, and since the onset of the famine, he had been receiving just eight pence a day, which was not enough to sustain his large family of six. He described struggling to feed his family, how his own malnutrition impeded his ability to do physical work, and mentioned having to beg for food from neighbors on occasion. He was forced to go begging to the Relief Committee in Ballymacoda and described how he had been brought by parish curate Rev. Eagar to the house of a woman in Ballymacoda who baked and sold bread and that he had been given two shillings worth of bread. In pure desperation for food, he also described his wife going out to cut Doolamaun (seaweed) and then boiling it with a little salt and eating it. The Miller family were living off this meal of seaweed in the days leading up to the death of the young boy. The references Miller makes here in his testimony to Mr. Gaggin of Greenland makes sense in the context of Ballymacoda. The Gaggin’s held extensive landholdings which they leased in the townland of Ring – much of which was a sublet of land which they had leased from the Marquis of Thomond, one of the main landlords in the area. Griffith’s Valuation of Ireland, completed for Cork in 1853, lists Gaggin’s extensive holdings in the townland of Ring. The newspaper clipping seen here also references the Miller’s home of Ring being ‘opposite Cable Island’, which was common spelling for ‘Capel’ Island at the time, so we can be sure the Millers were from Ballymacoda.

Thomas Miller’s wife, Johanna, was the last witness to be called at the inquest. Described as ‘a wretched looking poor woman, with a sickly infant at her breast’, she stated that the reason she was selling the corpse was ‘from want’. She recalled going to the landlord Gaggin and begging for a few turnips for her children to eat but being told that the last of them were in the boiler for the horses. Mrs. Miller described stealing some for her family to eat anyway and described how she would have ‘eat the cat from hunger’.

The Jury in the inquest having heard all the evidence ultimately returned a verdict of the boy having died of starvation.

I am certain that none of us today can truly imagine the scenario faced by the Miller family from Ring, Ballymacoda in 1847. They were driven to an insane act by pure desperation for food, and ultimately the desire for survival of themselves and their family. They, like so many others in East Cork and Ireland, had been entirely dependent on the potato to feed their large household and pay the rent. When the blight first arrived, they likely clung to what little savings they had, hoping the scourge would pass. But by the spring of 1847, nothing remained: the potatoes were spoiled, the livestock sold, the rent in arrears, and the children visibly wasting away from hunger.

This was during a dreadful period when the very fabric of rural Ireland seemed to tear at the seams, and a period that is certainly justified by its name of Black ’47.

References & Further Information

“So sad in themselves”: the impact of the Great Famine, RTÉ, available online at https://www.rte.ie/history/post-famine/2020/0909/1164237-so-sad-in-themselves-the-impact-of-the-great-famine/

Irish Potato Famine: A Tragic Chapter in Ireland’s History, History Cooperative, available online at https://historycooperative.org/journal/the-irish-famine/

Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier, Tuesday, 2nd February 1847

Cork Examiner, Wednesday, 3rd February 1847

The Morning Chronicle, Thursday, 4th February 1847, Page 6

Ireland, Griffith’s Valuation, 1847-1864