The Public Houses of Ballymacoda have long served as a welcoming haven for both residents and passing travellers, anchoring the social fabric of the area through every season and era. From the moment one crossed the threshold, the comforting glow of the lamplight spilling onto the street on a crisp evening beckoned, drawing people together to share both a freshly poured pint and the warmth of good company. For generations, the gentle hum of conversation, punctuated by raucous bursts of laughter combined with the faint aroma of peat from the fireplace to create an atmosphere that was both convivial and steeped in tradition. Indeed, these were not just places to enjoy a drink; before the age of modern conveniences, they were vital centres of social, economic, and cultural life, where neighbours and travellers alike exchanged news, stories, and customs. The public house likewise served as the gathering place where generations commemorated the passing of loved ones – a tradition that continues to endure today. In this article, we will delve into the historical roots of Ballymacoda’s pub trade, particularly from the mid-19th century onwards.

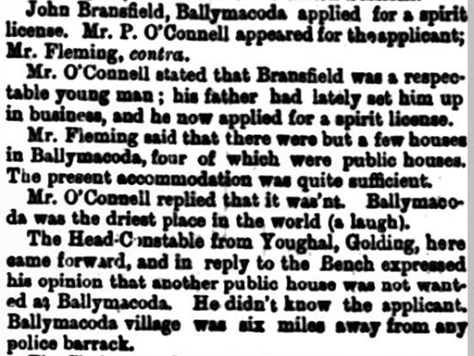

In the Cork Daily Herald on Saturday June 27th, 1868, we learn that John Bransfield has applied for a spirit license in Ballymacoda. Bransfield is described as ‘a respectable young man; his father had lately set him up in business’. There is some evidence to suggest that Bransfield came to Ballymacoda from nearby Midleton, and that he and his wife Margaret raised a large family here (at least 8 children according to the 1901 Census of Ireland records). In this report of his license application, we learn that there are already four public houses in the village, and that the Head R.I.C. Constable from Youghal, Constable Golding, opined that another public house was not wanted in Ballymacoda. It is also mentioned in this report that the nearest police barrack is six miles away, which confirms my previous research on the RIC in Ballymacoda that a barracks did not exist at this time. So, here we have a solid reference that there were four pubs in Ballymacoda in the 1860s. Bransfield’s license application on this occasion was adjourned. Later, in October 1868, the Cork Examiner mentions that the application had been refused.

In April 1870, we learn from the Cork Examiner that Maurice Bransfield (likely the father of John) has now applied for a new license in Ballymacoda. Again, it is mentioned in the report of the court sessions that there are already four public houses in Ballymacoda and another is not needed. The application for a new license is once again rejected, with the resident magistrate, Mr. Dennehy, mentioning that ‘if one of the four gave up, the applicant would get a license’. What the magistrate described here would later become law under the Licensing (Ireland) Act, of 1902, a law that is still on the Irish statue book today – and means that no new licenses can be granted, only existing licenses transferred.

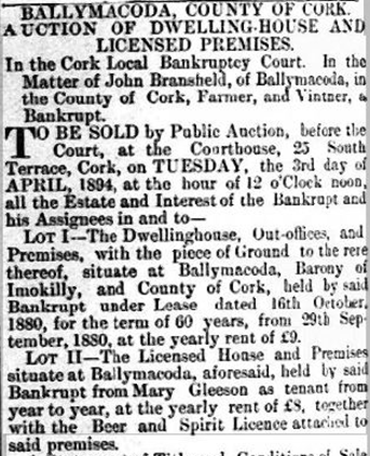

John Bransfield did eventually gain a license transfer – this is captured in the reporting from the Midleton Quarter Sessions in the Cork Constitution on November 1st, 1889. We can gain further insight into this through the many reports from 1893 and 1894 in relation to John Bransfield’s bankruptcy around that time. The notice of the auction of Bransfield’s holdings, which mentions him as a being a Vintner and a Farmer, that appeared in many newspaper reports of his insolvency at the time mentioned that he held a licensed premises from Mary Gleeson year to year for £8. However, the license, as we shall see, was the license from Power’s public house.

In a report of proceedings at the local bankruptcy court carried in the Cork Constitution on November 17th, 1893, we learn that the scenario of Bransfield’s license in Ballymacoda is complex. The license was originally held by Ellen Power, from whom Bransfield purchased it (the records of the Castlemartyr Petty Sessions confirm the existence of Power’s public house in Ballymacoda). However, as part of the license purchase, Mrs. Power was forgiven a sum of money she owed to Thomas S. Coppinger. Coppinger was a well-known and very wealthy merchant from nearby Midleton, and was the local agent of Cork city based brewery Beamish & Crawford. Further under the agreement, dated November 16th, 1888, John Bransfield agreed that he would only deal with Coppinger for porter and ale, and that he would keep his licensed premises in Ballymacoda as a going concern. As part of Bransfield’s bankruptcy, Coppinger was making a claim on the license and his solicitors contended that whoever took over the premises should now be bound to the agreement with Coppinger and only do business with him for porter and ale. The judge in the case, Judge Neligan, reserved judgement, commenting what seemed like his dubiousness ‘that the house must always be used as a public house, and that the covenant should be operative, say, for fifty or a hundred years, long after Bransfield had ceased to exist’. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find further contemporaneous reports that confirm the judge’s final decision, but nonetheless this is very interesting.

The records of the Castlemartyr Petty Sessions are a valuable source of information with regards the public houses of Ballymacoda. These court sessions of the 19th and early 20th century Ireland formed a cornerstone of the local judicial system. These sessions, typically held by justices of the peace (JPs), were central to rural and urban governance, providing a relatively accessible and cost-effective means of maintaining law and order within communities. Several court reports from the records of the Castlemartyr Petty Sessions from the 1870s tell us that the public houses in Ballymacoda at that time were: Power’s, Cotter’s, Gumbleton’s and Walsh’s. There are many examples listing offences relating to public houses in Ballymacoda, which we can use to confirm their existence at specific times. An example of this is the petty sessions held on October 15th, 1886. At these sessions Ellen Power was fined for ‘having her licensed premises at Ballymacoda open for the sale of intoxicating liquor on Sunday the 5th September 1886’. Along with the publican herself, John Donohoe of Gortavadda, William Aher of Ballymacoda, Mary Lynch of Ballymacoda, and Mary Brien of Ballyfleming were fined for being present in Power’s public house on the same day. Interestingly, Ellen Power was fined one shilling for being open and one shilling costs, while the four customers who were present in the pub were given a larger fine of five shillings each and one shilling costs.

Another example of this offence in the records is the aforementioned publican John Bransfield, who was fined twenty shillings for having his premises in Ballymacoda open on Sunday March 23rd, 1890. Bransfield was before the court for the same offence again on December 23rd of the same year, and again in May 1891.

The Guinness Trade Ledgers (1860-1960) are another good source of information relating to public houses in Ireland. These ledgers were meticulously maintained by Guinness, capturing the essence of their sales and personnel records over a century. Entries were often handwritten during the earlier years, and as the years progressed, the ledger entries were typed. The entries for 1913-1918 which summarize the deliveries to Ballymacoda show three public houses receiving deliveries of Guinness during those years – E. A. McLoughlin, John O’Donoghue, and James Gumbleton. Interestingly there are no orders at all for 1913 in the ledgers, and I can find no records in the ledgers at all before 1914. Were all the pubs ‘Beamish houses’ before then I wonder? As we have seen when discussing John Bransfield earlier, we know that Thomas Coppinger acting as local agent of Beamish and Crawford had exclusivity in at least one pub in Ballymacoda.

In 1924, the ledger entries for Ballymacoda reveal deliveries of Guinness to Gumbleton’s, McLoughlin’s, and O’Donoghue’s pubs. Cotter’s appears from the 1925 ledger onwards which perhaps means that they didn’t stock Guinness before that. The quantities in the ledger entries are listed as ‘Hhds.’, short for ‘Hogshead’, which was a large wooden cask. According to Guinness, the capacity of one Hogshead was approximately 416 pints.

To summarize our journey up to this point:

- In the 1860s and 1870s we know based on newspaper reports of the license aspirations of John Bransfield that there were four public houses in Ballymacoda.

- Combined with the records of the Castlemartyr Petty Court Sessions, we can ascertain that these were: Power’s, Cotter’s, Gumbleton’s and Walsh’s.

- In the late 1880s John Bransfield acquired Powers from licensee Ellen Power.

- The Guinness Trade Ledgers from 1913 tell us that there were deliveries of Guinness to O’Donoghue’s, Gumbleton’s and McLoughlin’s. Cotter’s also existed at this time but may not have stocked Guinness up to 1924 when those entries first appeared in the Guinness Trade Ledgers, or an alternative theory is that Cotter’s was closed and not operating as a public house for a period of time.

In terms of how the public houses of the 1860s evolved into the 20th and 21st centuries, it progressed as follows:

- Cotter’s → Finn’s – the Finn family bought Cotter’s around 1984 and then opened it up as Finn’s Tavern in April 1986.

- Walsh’s → McLoughlin’s → Daly’s – There are no McLoughlin’s living in Ballymacoda in the 1901 census. Edward McLoughlin Snr. came to Ballymacoda as an R.I.C. Constable (he was born in Co. Roscommon) – his entry in the 1911 census, showing him living in Ballymacoda mentions his occupation as ‘retired policeman’. In the same 1911 census data, his wife, Elizabeth McLoughlin’s occupation is listed as ‘publican’. This indicates that sometime between 1901 and 1911 the McLoughlin family bought Walsh’s public house. Dave Daly bought McLoughlin’s in 1990, and it remained open up until around 2010.

- Power’s → Bransfield’s → O’Donoghue’s – I would posit that O’Donoghue’s may have acquired what was Power’s/Bransfield’s during the bankruptcy of John Bransfield. O’Donoghue’s stopped trading in 2011.

- Gumbleton’s → Hopkin’s – Gumbleton’s became Hopkin’s and operated until the 1990s.

All but one public house are now sadly closed – since 2011, Finn’s Tavern has been the only public house in Ballymacoda. From these historical glimpses, it is clear that Ballymacoda’s public houses, which were once as numerous as the lamplights guiding travellers through the village, have evolved considerably over the centuries, transforming in name, ownership, and allegiance to breweries. Yet, through all the changes in licensing laws, economic fortunes, and personal family legacies, one abiding tradition remains: the central role of the pub as a communal gathering place, where residents mark life’s milestones, exchange stories, and nurture the tight bonds that define this close-knit community.

Though only Finn’s Tavern now stands to carry forward these customs, its continued presence in the heart of Ballymacoda ensures that the spirit of warm hospitality, once shared by many public houses, will hopefully endure for generations to come.

References & Further Information

Cork Daily Herald, Saturday June 27th, 1868

1901 & 1911 Census of Ireland Records

Cork Examiner, Tuesday, October 6th, 1868

Cork Constitution, November 1st, 1889, Mention of license transfer to John Bransfield in report of Midleton Quarter Sessions

Cork Constitution, November 17th, 1893, Details on John Bransfield’s Bankruptcy

Cork Constitution, March 22nd, 1894, Details on John Bransfield’s Bankruptcy

Ireland, Petty Session Court Registers, 1818-1919

Ireland, Guinness Trade Ledgers, 1860-1960

Credit to Elizabeth and Gillian Hyde for the photograph of the Beamish delivery to Cotter’s